“The most evil of humans is yet to be born.”

This sentence appears in Ferdinand Ossendowski’s book, Beasts, Men and Gods. Ossendowski’s work was published in 1922; if at that time the most evil of humans had not yet been born, the impression at the dawn of the 21st century is that humanity’s most wicked elements are not only already among us, but are in the full manifestation of their demonic powers, as evidenced by the abominable developments of globalism…

In this light, re-reading Ossendowski’s classic is far from a mere scholarly exercise; it can still provide useful indications for an esoteric interpretation of contemporary events.

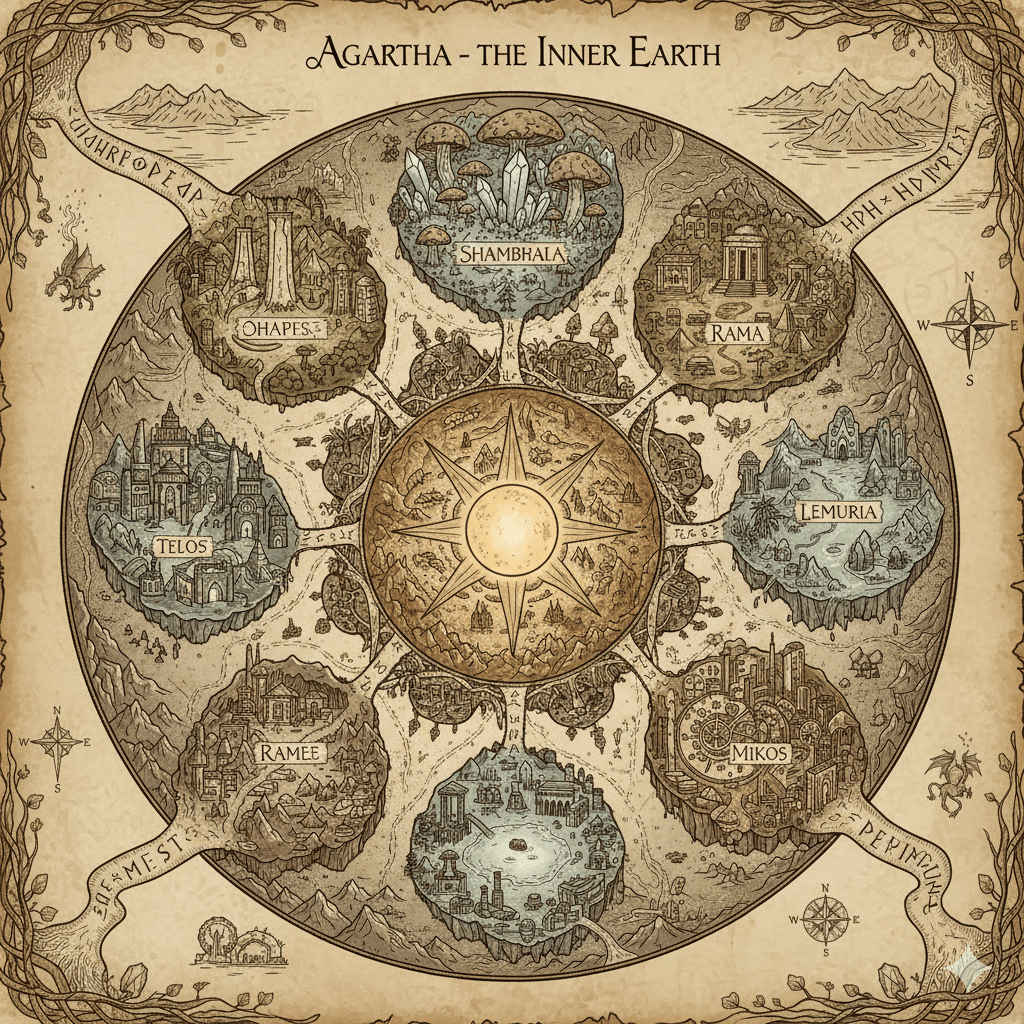

Louis de Maistre’s recent essay, Dans les coulisses de l’Agartha (“Behind the Scenes of Agartha”), is a wide-ranging study of the Polish author and his extraordinary adventure in the Asian wildlands. De Maistre’s book serves as a valid support for retracing the fascinating themes of Agartha and the King of the World—concepts made famous by René Guénon but already known through oral traditions and esoteric literature.

The events narrated in Beasts, Men and Gods, centered on the epic of Baron Ungern von Sternberg, are little known to the general public, yet they are by no means secondary. In those years, not only were the final phases of the Civil War between the Whites and the Reds unfolding in revolutionary Russia, but a crucial “chess game” for the control of Asia was being played between Russia, the British colonial power, China, and Japan. Official Soviet historiography depicted Ungern as a pawn manipulated by Japan, but the reality appears different: the “Mad Baron” was a romantic warrior driven by an unshakeable faith in counter-revolutionary ideals. Ungern von Sternberg, as is well known, intended to conquer Mongolia to use it as a base from which to unleash the Oriental masses against the West, which he held guilty of embracing the materialist ideologies of which Communism represented the most monstrous manifestation.

Ungern’s saga was, in practice, counterproductive to its original aims: the “Bloody Baron” indeed liberated Mongolia from the Chinese, only to be overwhelmed by the Bolsheviks. As a result, the Soviets seized the great Eastern nation without having to clash with the Chinese army. This represents the first instance of a nation being conquered by a Communist power.

Ossendowski’s book enjoyed extraordinary success during the interwar period, and the French translation of Beasts, Men and Gods was an exceptional cultural event. To present the work to the public, a round table was organized featuring the author, the orientalist René Grousset, the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, and the esotericist René Guénon.

The public wondered to what extent Ossendowski had taken the theme of Agartha from Saint-Yves d’Alveydre’s Mission de l’Inde, the book that had first disseminated the legend of Oriental origin in the West. Guénon argued for Ossendowski’s originality, though with less than convincing arguments. For his part, the Polish author denied having read Saint-Yves’ text, yet an analysis of his book raised significant doubts regarding Ossendowski’s good faith. Some travel experts noted substantial inconsistencies in his descriptions of places and distances. Furthermore, the narrative varied according to the editions published in different languages. Certain details were decidedly implausible: Ossendowski managed to escape extremely perilous situations with suspicious ease… Ossendowski himself, on some occasions, admitted to having written a somewhat fictionalized account.

In the Polish version of the book, a singular episode is reported in which the author, near Lake Tassoun, encounters a village inhabited by blonde-haired, blue-eyed individuals, said to be descendants of Venetian and Genoese merchants who traversed the area in the Middle Ages. Beyond the lack of verisimilitude of the episode itself, the somatic characteristics described do not suggest the typical features of Italians. Moreover, Ossendowski was always an author as prolific as he was shallow, demonstrating a superficial knowledge of historical events and Eastern religions.

Louis de Maistre reconstructs Ossendowski’s biographical details, which present many ambiguous and mysterious traits. Regarding his cultural formation, we know he always professed a fierce anti-communism, that he was a Modernist Catholic, and that politically he could be defined as a progressive liberal. Our author also seemed involved in the Sisson Documents affair—a collection of documents supporting a conspiracy theory intended to prove that the Russian Revolution had been incited by Germany to disengage the Eastern Front and concentrate all troops in the West. In general, the available biographical elements suggest that the Polish author may have carried out espionage for the White Front, and Louis de Maistre does not rule out the possibility that he played a double or triple game: his adventure in the East remains nothing short of miraculous…

A key figure on the Mongolian chessboard of that period was Dr. Gay, a veterinarian who certified the health of livestock and was therefore essential for the provisioning of troops. Ossendowski was particularly well-informed about Dr. Gay’s activities and was likely gathering intelligence on him. Baron Ungern would eventually condemn Dr. Gay and his entire family to death, convinced he was working for the enemy—though the veterinarian may have been a victim of unjustified suspicion. This episode suggests that Ossendowski was engaged in delicate intelligence missions and that his information was held in high regard by Ungern.

Some scholars have also hypothesized that Ossendowski’s hand assisted in the drafting of Order No. 15, the famous proclamation and call to arms with which Ungern intended to unleash the “Yellow Race” against the West. The rhetorical tone of the text suggests the intervention of someone with literary skill, rather than military men unaccustomed to writing.

Baron Ungern also possessed “proto-Nazi” traits: fiercely anti-Semitic, it is known that he ordered a pogrom against Jews after the conquest of Urga (Ulaanbaatar). However, in the English edition of Beasts, Men and Gods, this episode is silenced, and Ossendowski has Ungern claim that his closest collaborators are all Jewish. Louis de Maistre believes this part of the book is a total falsification of reality, performed by the author to make Ungern’s character more “acceptable” to the Anglo-Saxon public.

The theme of the King of the World, dear to fantastic literature, also took on unsettling meanings in its demonic reversal, to which Guénon alluded in his book dedicated to the subject. Ossendowski, in fact, returned to the topic in some of his writings, referring to the mysterious sovereign as the “Great Unknown” (Le Grand Inconnu). This title simultaneously recalled the Masonic theme of the “Unknown Superiors” (Supérieurs Inconnus) and the “Big Brother” mentioned by the Jewish thinker Jacob Frank. These references were part of an esoteric culture that was widespread at the time (and which can still help us understand many aspects of the contemporary world).

Louis de Maistre also examines hypotheses regarding the origin of the name Agharti. Saint-Yves wrote it as Aghartta, and the name Agharti might be derived from a location in Kazakhstan called Agartu (noting that in Turko-Mongolian languages, the final “u” is pronounced like the German “ü”). There is also a Hungarian location named Agard. Furthermore, we find the designation Agartus oppidum reported by Lucius Ampelius in the 3rd century, referring to an Egyptian city. On the other hand, Jacolliot recalled the name Asgard from Nordic myths, while Saint-Yves invoked the Hebrew ageret, meaning “epistle,” which would reference the Epistles of Paul.

The myth of Agharti even seduced certain Soviet intellectuals: as part of a scientific mission sent by communist authorities to the Kola Peninsula, the scientist Aleksandr Barchenko aimed, among other things, to explore and find a potential entrance to Agharti.

Even Ossendowski’s end is tied to an enigmatic event. On January 1, 1945, a Nazi officer visited the Polish author at his villa near Warsaw; the two spoke for several hours, and the German finally left the house with a copy of Beasts, Men and Gods. Witnesses and journalists of the time have put forward various hypotheses: the German officer might have been a relative of Baron Ungern, a certain Dollert who worked for the German secret services and who, after the war, allegedly became a Franciscan friar in Assisi. Inside the copy of the book, there may have been classified documents regarding the events Ossendowski had witnessed. However, these are merely speculations: on January 3, 1945, Ossendowski died, taking his potential secret knowledge of the King of the World to the grave. In the post-war period, the Polish communist regime banned the publication of Beasts, Men and Gods, and Polish readers were only able to rediscover its intriguing pages after the end of the Cold War.

Louis de Maistre’s essay is a fundamental reference for deepening our understanding of the events narrated by Ossendowski, even if much of the Polish author’s work and life remains shrouded in a veil of mystery. It is important, above all, to keep alive the interest in the epic narrated in Beasts, Men and Gods, not only for the fascinating theme of the King of the World—which maintains an ahistorical significance—but also for the circumstances in which the book was born. Ossendowski described an episode of the Russian Revolution, effectively recreating the apocalyptic atmosphere of those moments. Globalism is the logical development of Communism, and the climate of hatred and violence described by Ossendowski is very similar to the one breathed within globalization today.

***

Louis de Maistre, Dans les coulisses de l’Agartha. L’extraordinaire mission de Ferdinand Anton Ossendowski en Mongolie, Archè, Milano 2010, p.392