Tolstoy: The Genius of War and Peace and the Moralist “Mess” Post-Anna Karenina

___________________________________

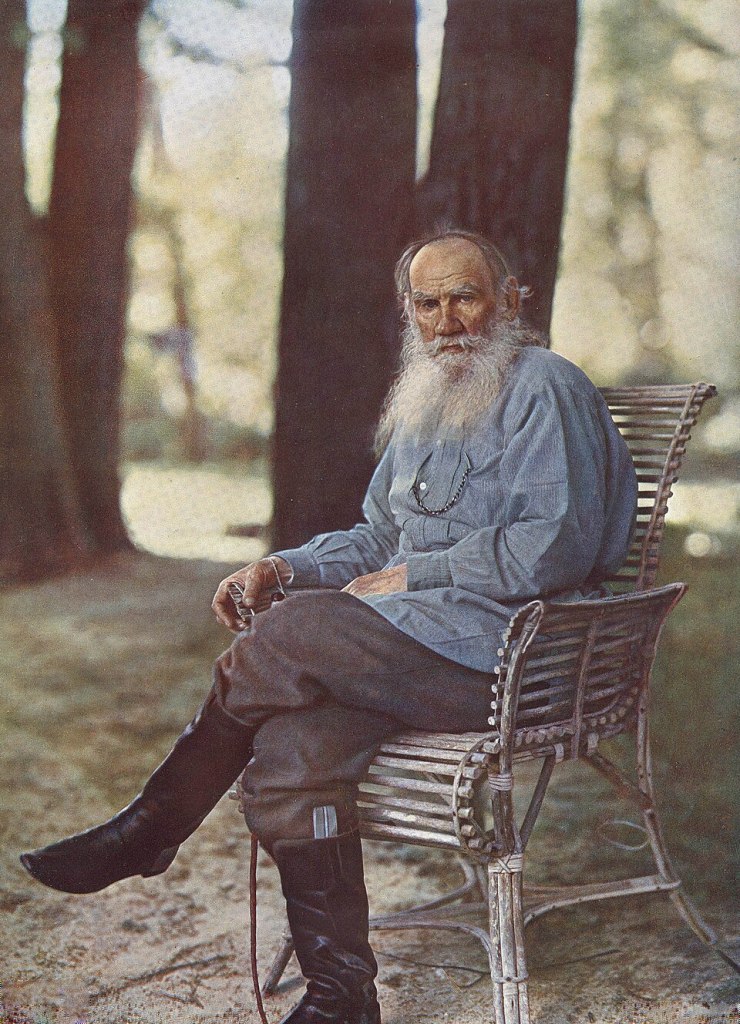

Leo Tolstoy is a writer whose greatness needs no introduction. The human condition is painted with extraordinary depth and power in War and Peace (1867). Contrary to what our contemporary image of Tolstoy might suggest, War and Peace is not a pacifist manifesto at all. The idle Russian bourgeoisie, immersed in balls, philosophical discussions, and socialites, is incapable of perceiving the gravity of the Napoleonic invasion; only the defeat and the horror of Austerlitz awaken the protagonists’ humanity, allowing them to understand the meaning of existence (both individual and collective) in a Russia threatened by destruction.

It is in this confrontation with necessity that Tolstoy is a genius: Napoleon is not an imaginary tyrant, but a man of flesh and blood; Russia is not a mere stage, it is life, it is the motherland. War is not a game, it is a necessity. Action, pain, commitment, sacrifice—far removed from balls and receptions. Here lies the Tolstoy one can admire without reservation: the one who captures man in the drama of his contradictions, who sees life as tragedy and not as mere material for moral lessons, and who idealizes neither the individual nor society, but observes them in their primary needs. To resist, to exist, to survive. To live.

Faced with this masterpiece, understanding the post-1870 Tolstoy appears almost impossible. His sudden conversion to a pacifism as absolute as it was abstract, his post-Christian moral doctrine, and his rejection of the Orthodox Church seem alien to the tragic experience he himself had masterfully represented. It is a stunning paradox: the author who understood that history and necessity impose sometimes terrible choices, the author who showed the inexorability of the confrontation with reality, becomes a moralist who imposes rules that ignore the concreteness of the world.

Applied to Russia, the pacifism of the Tolstoy of the late 1870s is absurd: a country repeatedly threatened in its very existence cannot afford “thin broths” of good intentions masked as abstract ethical ideals. Such an attitude can only be understood as the consequence of a terrible spiritual crisis: the shock of the destructive power of the individual and the unease regarding the violence it can generate within society.

In Anna Karenina (1878), we observe, almost experimentally, what triggers this crisis in Tolstoy’s soul: Anna’s vital and sexual passion for Vronsky. At first glance, the plot might seem banal: a young married woman falls in love with another man. “Big deal,” one might say. But Tolstoy transforms this banality into an existential catastrophe. Anna is certainly no naïve girl: she is an intelligent woman who knows the consequences of her actions, knows what it means to break conventions and live according to her own desire. And yet, tragedy manifests. Anna destroys those around her, destroys herself, and society reacts like an immune system imposing its sanctions.

In his late moral revolution, passion, vital force, and sexual desire become suspicious to Tolstoy—almost immoral. What the novelist had celebrated as a revelation of human life, the moralist now condemns. Sexuality, passion, and desire become sources of chaos and generate a violent response regardless of intent. Anna’s tragedy—the fact that she simply wanted to be happy and that this caused victims around and within her—becomes, for Tolstoy, the symbol of the danger of individual freedom. The moral solution proposed in his late writings, particularly in The Kingdom of God is Within You, consists of imposing an absolute curb on this freedom, subordinating the individual to a universal moral law, and denying violence and what vital desire can generate. Tolstoy denies freedom.

This transition from the novelist to the moralist represents a profound reversal: the genius capable of perceiving and rendering the complexity of life becomes the “guru” who simplifies what he had observed in all its richness ten years prior. Anna Karenina becomes a precursor laboratory for the moral doctrine that follows: the passion, error, and tragedy of the individual are the experiment that leads Tolstoy to want to uproot the destructive power of the individual and society.

Thus, the post-Anna Karenina Tolstoy loses the sense of the truly tragic. Life, previously a subject of infinite and nuanced observation, becomes a terrain for abstract and prescriptive morality. Passion, which he had understood and represented with such acumen, becomes suspect. The conflict between individual and society, between freedom and necessity, becomes a problem to be solved with abstract ethical principles, no longer a tragedy to be contemplated.

It is impossible, when reading Tolstoy, to separate admiration for the novelist from criticism of the moralist. War and Peace remains a pinnacle of the depth and complexity of the human condition, a monument to the greatness and fragility of man in the face of history. Anna Karenina, while admirable as a novel, anticipates the Tolstoy who rejects what he once celebrated: passion, desire, and irrepressible freedom. The radical pacifism and absolute morality of his late writings are the logical consequence of this flight from concrete life.

But Tolstoy’s moral fall is not limited to pacifism. His religious contradictions—denying the divinity of Christ, rejecting the Trinity, and transforming faith into a personal code—reveal a dangerous dissociation between art and doctrine. He claims to impart absolute ethical truths while pretending that the Gospel does not also speak of the resurrection of Jesus. He claims to found his morality on a Gospel that exists nowhere but in his own mind.

The post-Anna Karenina Tolstoy is a moralist who sacrifices the coherence and richness of human experience on the altar of a depersonalized and self-referential spirituality. Tolstoy remains an extraordinary and paradoxical author. However, the post-Anna Karenina Tolstoy—radical pacifist, absolute moralist, post-Christian—shows how a genius can lose his way, replacing the depth of the great artist’s gaze with a flat and abstract moral ideal, thereby losing contact with the complexity of life.

***

Luca Costa

***

Text translated from Italian into English by Google Gemini in 2026